There was no thought, let alone premonition, of founding a company, avocation or industry in 1952 when I sat down in an apartment in Catonsville, Maryland, to design what ultimately became known as Tactics, the first modern board wargame.

To suggest that I had visions of a “Charles Roberts Award” is little short of ludicrous. To think that dreams of creating the top-selling wargarne were dancing in my head is absurd. Nothing that happened afterwards was planned or intended. It has been said that Great Britain acquired her Empire in a fit of absentmindedness and, as I survey a teeming industry replete with competing companies, conventions, tournaments, publications, personalities, traditions and historic events, the parallel seems apt.

To be conversant with the Principles of War is to a soldier what the Bible is to a clergyman. The Bible, however, may be readily perused. . . wars are somewhat harder to come by.

Thus I decided that I would practice war on a board as well as the training field and learn the nuances of the Principles of War in a context that was less noisy. Since there were no such wargames available, I had to design my own and, while about it, might as well command Army Groups as mere platoons.

The Korean War was winding down, the army suspended Competitive Tours for a few years, my decision to be a career soldier went awry and the game became a classic. All by accident.

Two mapboards were designed for my first wargame to provide a maximum selection of tactical and strategic situations in a variety of terrain features. The second map- board was originally published in Tactics in 1954 and, revised, in Tactics II in 1958. Until this year (1983), the first or truly original mapboard has never been published. It is coming out under Avalon Hill’s imprint with rules from the early Tactics.

Whatever verdict history will deliver on my capabilities as a publisher, game designer or, for that matter, soldier, it is certain that I will never be acclaimed as a geologist. All the rivers on both mapboards run in the wrong direction. Further, having no idea that the game would ever be published, I simply used handy blank boards of an odd size that do not cut well out of standard paper sizes and so created a “standard” size that has chagrined printers for decades.

I soon learned that playing a realistic game had very real training value and at least some predictive aspects. The former, to me at least, is the most fascinating. . . the latter must be viewed with great caution, especially in wargames. There began a focus in my mind on the training and, indeed, educational nature of realistic simulations that became a jealous mistress which in the end played a major role in the demise of Avalon Hill during my tenure.

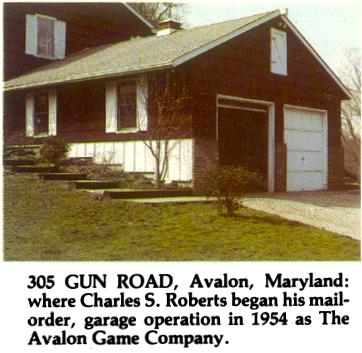

Almost as a lark, in 1954 I decided to publish Tactics as a part time venture under the corporate name The Avalon Game Company, the name coming from the site of an historic village near my home. Memory, in the absence of records, tells me about 2, 000 games were sold and the effort either netted or lost thirty dollars. I learned something about the marketing of games in this reconnaissance-in-force and four years later decided to have a go on a larger and more serious scale. Needing a new charter, I applied for the same name. At the last minute a conflict was apparent with a local firm and the name Avalon Hill was selected simply because I live on it. . . to this day, as a matter of fact.

Let me emphasize that Avalon Hill was not founded to pioneer in wargaming. I was convinced that there was a market for realistic games of specialty format, designed to appeal to those who enjoy intellectual challenges and prefer competition wherein skill is a primary virtue.

Gettysburg was selected as a subject because of the upcoming Civil War Centennial, a wise choice because the celebration was widely publicized. Gettysburg, by the by, was notable because it was the first modern historic wargame. More ruefully, it was also the first and last wargame to be introduced with no playtesting whatsoever, an omission which plagued it through numerous futile redesigns. However, it sold very well and in spite of its flaws has to be counted as a successful title.

Dispatcher was designed to appeal to rail fans and was the first of a long line of “civilian” titles even though it was not a good seller. Curiously, the decision to re- publish Tactics as Tactics II was made at the last minute simply to fill out the opening line. I really didn’t think it would sell well, not the last time my sales forecasting missed the mark.

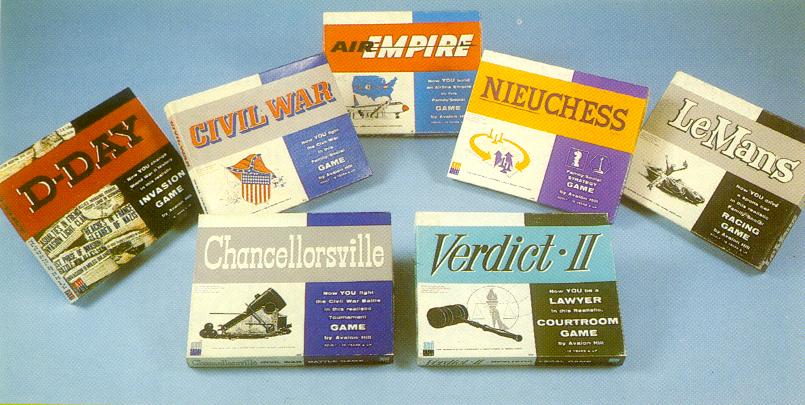

Having certain skills in marketing and administration, and a talent for selecting fine executives, my business grew rapidly. While noting that the wargames tended to sell best, we continued to publish a variety of civilian titles such as Verdict, Management, Le Mans, Verdict II, Air Empire, Word Power and, of course, Thomas N. Shaw’s superb Baseball Strategy and Football Strategy. Industry historians are always surprised when I point out that Avalon Hill published more civilian titles than wargames during its first five years.

Also, I devoted enormous amounts of my time and corporate resources to chase the elusive dream of educational gaming. For example, Game/Train, the first tactical board wargame, was designed to be a squad and platoon level training aid for combat leaders, not a consumer title. This devotion produced nothing but expense. The Golden Fleece was never found.

Worse, I was slow to realize that there was a budding wargaming hobby out there. When this development became plain even to me, plans gushed forth for publications, directories of players, encouragement of club formation and other devices to give impetus to the growth of a hobby. Every one of these projects came to pass under later management. . . at that time, sad to say, the business was in trouble with plummeting sales and we could not gather the resources to capitalize on the true opportunity.

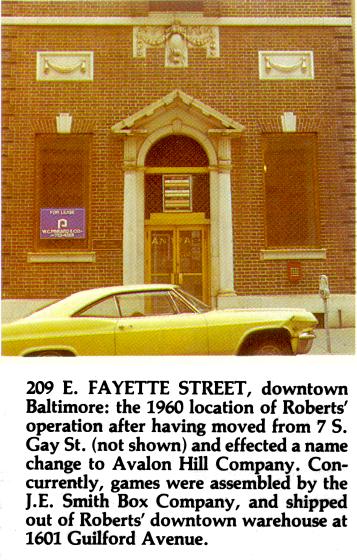

The sharp decline in sales had many causes. The rise of the discount house tore apart traditional methods of bringing goods to market; a nasty business recession it in 1960-61, toy industry distribution channels always react with a “hero or bum” syndrome when one has come off a bad year and we had one in 1961; runaway TV promotion of toys, ultimately suicidal even to the leaders, swept aside lesser companies; too many low-selling civilian titles made our line imbalanced; our financial base was highly leveraged, very nice going up but terrible going down. . . all these and other factors combined to press us into a fight for survival for two years. In the Fall of 1962 we thought we had turned it round, an estimate that missed by two or so years.

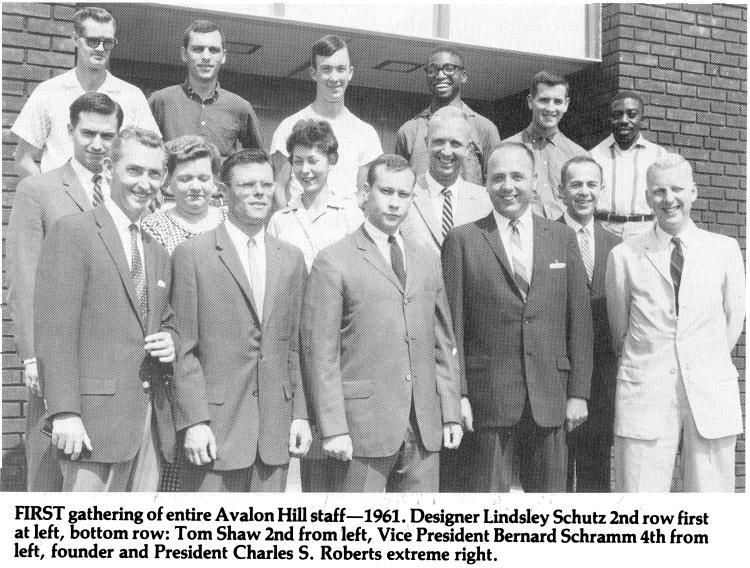

All stories have unsung heroes and here is a list of managers, investors, suppliers, salesmen and others who played key roles in the creation and building of Avalon Hill: Bernard C. Schramm, Jr. and Thomas N. Shaw, two of the most loyal and intelligent gentlemen on earth; Bernie Graf, Mary Busch, Pete Quigley, Page Nelson, Warren Somerville, Dave Marks, Dave Krotman, Hank Dubs, Pat Joynes, Bud Weitzel, Earl Sparling, Bucky Walsh and others whose names would appear but for the fragility of my memory.

In spite of the best efforts of these stalwart people, by the end of 1963 we were in effect working for our creditors. Of those creditors, none of whom expressed anything other than sympathy for my situation, only Eric Dott bothered to visit our offices and receive a briefing. Within minutes he gasped the essential facts and the long range opportunities. Although a small creditor, he arranged for a continuation of the business and I turned over control to a committee.

Bernie Schramm and I declined kind offers to stay. Tom Shaw later accepted against the sterling advice of both Bernie and myself, a fair warning to those who would ask for my opinions in the future. In the early fifties Eric Dott and I had formed a tiny company to explore an idea which did not plan out. Now Eric Dott, relatively unknown in the field to this day, provided the energy and wisdom to rebuild and create a highly successful enterprise which is of great service to its owners, employees, customers and community. As responsibility for the decline of the company rests solely upon me, that I played a tiny role in this rebirth is a source of some personal satisfaction.

The problems of wargame design in the early years were considerable. Tactics introduced a totally new method of play which had no parallel in games designed to that point and potential players had difficulty in grasping the simple mechanics. It was revolutionary to say that you could move up to all of your pieces on a turn, that movement up to certain limits was at the player’s option and that the resolution of combat was at the throw of a die compared to a table of varying results. As simple as this sounds now, the new player had to push aside his chess-and-checkers mindset and learn to walk again. After he learned to walk, he had to master the intellectual challenge of the game itself usually without the benefit of an experienced opponent. The miracle is that the early player managed to play at all, burdened as he was in many cases with poorly written instructions.

The lack of basic skills on the part of the typical purchaser of an early wargame severely limited the designer, forcing him to simplify the play to get the game played at all. Today there is a great body of experienced players who can find opponents with ease and the designer can take wing without worrying about trivialities. Also, today’s designer has readily available historic data not so easy to find in the early years. Game design today, enhanced by the evolution of improved graphics, is by no means an easy task, but at least the creator can assume the purchaser will not have difficulty getting the lid off the box.

It takes nothing from the brilliant achievements of, say, a James Dunnigan, to point out that he had an audience of players who had graduated from basic training through the efforts of those who had gone before.

Inevitably I am asked questions of a certain genre which are valid and deserve answers.

Have I done any design work since the early sixties? Yes. . . during the 1970s I designed what I consider to be a second generation board wargame and hope to bring it to the point of publication in the near future. Whether the market will accept this design as second generation remains to be seen, but with luck perhaps I can win my own award! Let me hasten to point out that, as our early work helped today’s designers, their work in turn will help me to offer an advanced design.

What is my view of the typical “state of the art” wargame? Outstanding, subject to some reservations implicit in the preceding paragraph. Few soldiers play wargames; fewer still design them. Why? Without being too Delphic, I wonder if the typical player knows what a soldier really is and what he faces. In no way meaning to be facetious, I recommend the reading of From Here to Eternity and the study of Prewitt, the true soldier. One cannot design a proper simulation without at least a tiny insight into the attitudes of the people involved and the milieu in which they operate. Of course, this is not a proper forum for such a discussion in detail. . . as a point of interest, one of my goals in life is to expand upon this theme in a series of articles leading to a book (if I can find a publisher!). I broach this subject with some trepidation. In the hallowed pages of the Marine Corps Gazette in the mid-fifties I crossed swords with Captain Liddell Hart in a series of articles exploring the future of war, at the conclusion of which he held the high ground and I the hilt of my sword sans blade, with nothing for solace but a kind note from him .suggesting that perhaps we were not all that far apart. With my luck, Sir Basil’s ghost will spring out at the wrong time.

How do you regard the title “Father of Wargaming?” With faint amusement. May I note that I would rather be known for something that was the result of deliberate effort.

What of your career since 1963? I spent several years in big corporate life, followed by about ten years as head of the publishing division of a Baltimore house specializing in publishing to the Catholic market and, for the last ten years, as owner-with-wife of Barnard, Roberts & Co., Inc., again publishing primarily to the Catholic market. Thus for some twenty years I have been a publisher to the Catholic Church even though not a Catholic and not, shall we say, with a reputation of being over religious, For the record, I love it.

Irony and history are handmaidens. Catonsville was an unknown small town on the out skirts of Baltimore until the Berrigans and their Catonsville Nine put it on the map, taking issue with their society and own Church. Catonsville is also the birthplace of modern wargaming, sired by a non-Catholic who has spend most of his career as a servant to the same Church.

As a publisher, one has to say that it would make poor fiction indeed.

This article was written by Charles S. Roberts in 1983.